Creative inspiration in historical fiction

Historical research is all very well, but how can you make your novel come alive, and transport the reader viscerally to another time? Sometimes you need a more tactile or atmospheric prompt to help you imagine a scene and convey it on the page to your reader. Here are seven ideas that have worked for me.

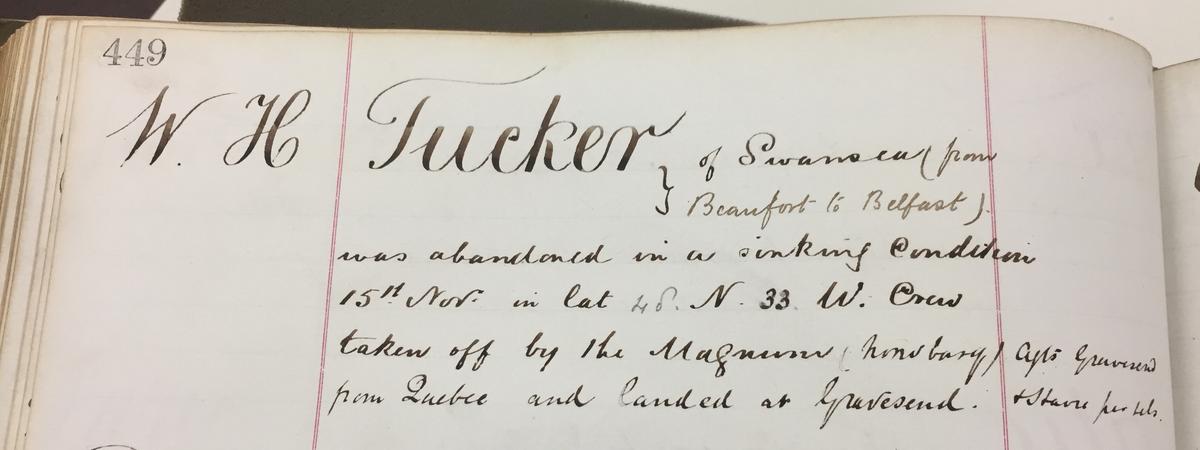

Public records and private documents

At the beginning of my journey in researching Copperopolis, I requested to read Lloyds Captain’s Registers in the London Metropolitan Archive. I wasn’t prepared for the size of the volume, propped up on foam cushions. I turned the heavy, yellowed pages with respect until I found John Clement’s voyage history, neatly inscribed in copperplate, coded in black, blue and red ink. I imagined the clerk scratching away, and the magnitude of the sweat and effort that lay behind the initials ‘SP” for South Pacific, which could only be reached by rounding Cape Horn.

Researching my family history, I had access to letters, documents, wedding photographs, wills and pilot certificates, each of which had meant so much to the lives of my ancestors. And my grandfather had kept his two inch thick top secret Operation Neptune instructions, annotated with his own pencil markings for the codes that applied to him.

Locations

Headlands and beaches in Gower have changed little in the last two centuries, making it easy to imagine my characters galloping along the tideline or scouring the horizon for a ship. Pubs, docks, houses, markets, churches and public buildings are imbued with the history of people who frequented them. Small details of doors, lintels, windows or furniture can evoke the experience of being present in a space.

Clothing

Museums like the V&A provide an insight into what people wore and how it may have affected their daily life. While researching WW1, I visited the Imperial War Museum and saw the outfit that War ministry typists wore. If you can’t get to a physical museum, books like “How to read a dress” or “How to read a suit” by Lydia Edwards provide plenty of detail for fashions of the last 500 years.

Objects

Master mariners in the 19th century relied heavily on a sextant to calculate their position out in the middle of the ocean. I pored over sextants in museums and even watched videos on how to take a sight. My second novel is set partly in New Zealand, so I visited the British Museum to examine cloaks, and tikis (good luck charms). Handling a tiki that is still in the family prompted me to think about how it might feel to wear one next to the skin.

Contemporary letters and articles, first person accounts

Letters, diaries and articles from the time are gold dust if you want an insight into how people expressed themselves when faced with challenging situations. I have freely incorporated many anecdotes published in “The Swansea Copper barques and Cape Horners” by Joanna Greenlaw for my own fictional characters. When I was researching the suffragettes for my second novel someone gave me “Suffragettes: The Fight for Votes for Women” by Joyce Marlow which is packed with contemporary articles, letters and pamphlets. I picked up glorious detail such as women wrapping newspapers round their waists under their dresses so they didn’t get bruised when manhandled by policemen during protests.

Old photos and postcards

Postcards and newspaper photographs of streets and towns provide detail of shop fronts, vehicles, and clothing that you can build into your scenes. Family photo albums may be formal but allow you to stare into someone’s soul and imagine them speaking.

Films, plays, TV series

A film, play or TV drama or documentary series set in a similar era or location can yield multiple clues on clothing, habits, how people of that time moved, spoke and reacted to each other. Use your judgement to decide what is authentic and what is anachronistic.

Which of these techniques work for you in your historical fiction writing? Share your thoughts here or find me on social media.